Bangladesh ousted an autocrat in 2024. Can it pull off a democratic reset now?

The sun is setting behind the mahogany trees in the schoolyard when the candidate rises to speak. Above him, lashed to the canopy over the stage, hang sheaves of unhusked rice, the symbol of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party.

Mirza Fakhrul Alamgir, the BNP’s secretary-general, is a veteran of Bangladesh’s turbulent politics. This is his 16th campaign stop of the day, another chance to plug his party and his candidacy in Thakurgaon, his parliamentary district. But first, he wants to remind the hundreds of men, women, and children sitting in rows of plastic chairs why this election is different.

“This time, we will cast our own votes,” he says. “Our own votes.”

Why We Wrote This

Bangladesh made a break with authoritarianism in 2024, and since then, some of its interim government’s lofty goals have fallen short. But upcoming elections offer a chance for a democratic reset.

After 15 years of one-party rule legitimized by sham elections, the promise that votes will be cast and counted fairly is a potent one. The Feb. 12 election is seen as a crucial step toward a restoration of multiparty democracy in Bangladesh – and a marker of how far it has come since a student-led uprising in the summer of 2024 drew global attention.

The uprising, which was brutally suppressed by Bangladesh security forces and paramilitaries with the loss of at least 1,400 lives, unseated Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who had been in power since 2009. In August 2024, she fled into exile in India, leaving behind a shaken country and a brittle economy that an interim civilian administration has struggled at times to govern.

Now, that interim government – installed with support from student activists and the military – is holding an election to select a 350-member Parliament that will form a new government. Voters will also be asked to approve a set of constitutional reforms that are designed to guard against autocratic backsliding and codify some of the demands for change that emerged from the uprising. These include term limits for lawmakers, a more powerful presidency to check the prime minister’s authority, and measures to counter corruption and conflicts of interest.

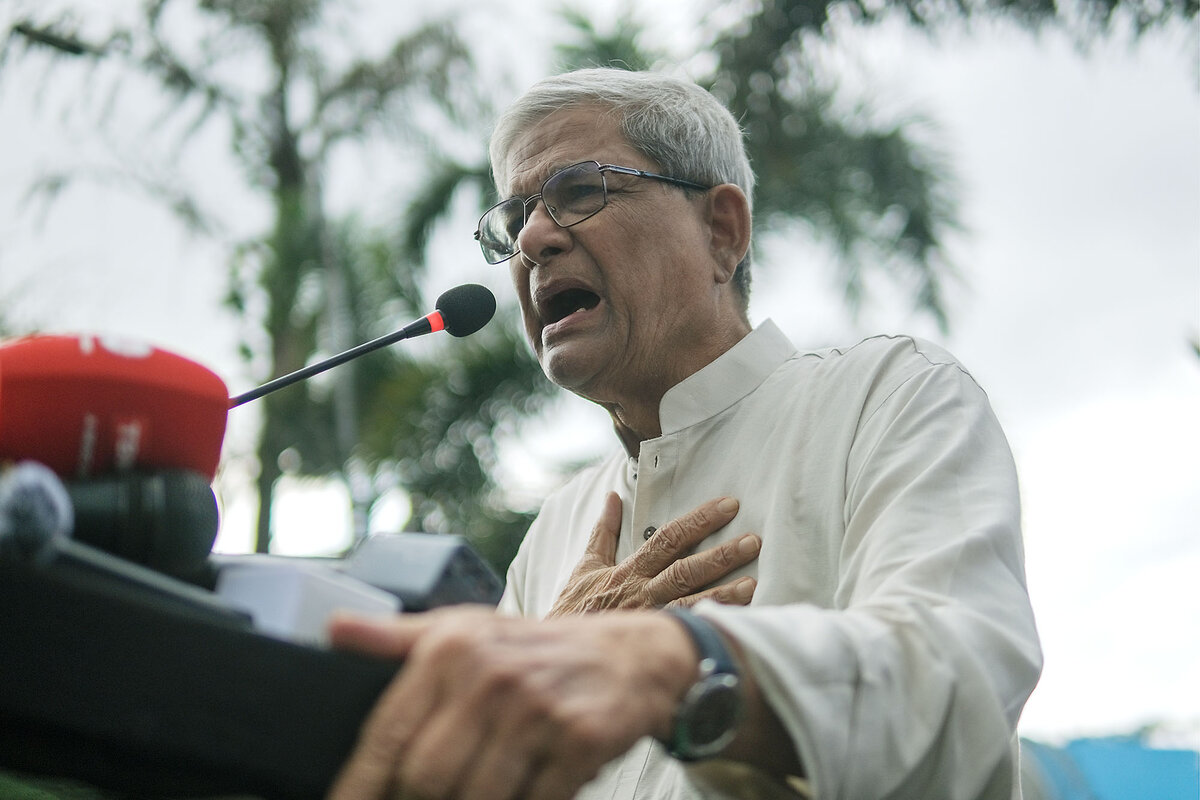

Syed Mahamudur Rahman/NurPhoto/Reuters/File

Mirza Fakhrul Alamgir, secretary-general of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, speaks in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Aug. 22, 2025.

The reforms were hashed out by leaders from across the political spectrum – an achievement by itself, given the internecine politics of a country whose bloody birth in 1971 remains a contested history. But, as the United States has found out, checks and balances in a political system only matter as far as politicians feel bound by the rules and norms put in place.

“We all recognize the fact that no matter how [many] reforms are undertaken in the electoral space. ... if the political parties don’t themselves reform in the right direction, it’s going to be tough,” says Mir Nadia Nivin, who chaired the interim government’s electoral reform commission.

Navigating the “Bermuda Triangle” period

On the streets near Dhaka University, the epicenter of the 2024 uprising, walls painted with anti-regime artwork are starting to fade. A new banknote issued this week features an image of a student protester. But that feels to some like a fallen star from an unfulfilled revolution.

“The feeling is quite mixed. I don’t feel that we’re in a good situation,” says Sayma Nowshin Suga, who is studying Japanese at Dhaka University. Looking back, she says, “We thought Bangladesh would become a better place.” Now, she worries about mob violence in Dhaka and other cities and rising religious intolerance against non-Muslims, which an interim government has often been reluctant to confront.

Ms. Nivin, a former U.N. official who worked in Myanmar and Afghanistan, says the Arab Spring is a reminder of how street movements that coalesce to end a regime don’t always pan out. “The Bermuda Triangle of all successful youth-led or mass movement revolutions is post-revolution when you’re making the democratic transition,” she says.

Bangladesh became the first in a series of Generation Z-led protests in 2024 and 2025, ranging from Peru to Indonesia. Many borrowed inspiration and tactics from other movements, becoming a sort of chain reaction carried by online activism. Not all succeeded as Bangladesh’s movement did in bringing down a government.

Rajib Dhar/AP/File

Students protest in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Aug. 13, 2024. A wave of violent protests in July and August 2024 led to about 1,400 deaths and the ouster of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina.

But in Nepal, anti-government protests last September did force a change at the top. A similar rupture shook Sri Lanka in 2022, forcing out a president from a powerful family who had fumbled an economic crisis.

In all three South Asian countries, say analysts, anger at the political class was fueled by a lack of economic opportunities in a system seen as rigged by insiders. Bangladesh’s protests began over political patronage in government hiring of graduates.

Nepal is holding elections next month under a caretaker government led by a judge. That’s a much quicker turnaround than in Bangladesh, says Paul Staniland, a political scientist at the University of Chicago who studies South Asia. The idea was to “find some stability and political order and then try ... a partial reset,” he says.

Bangladesh’s interim government took a different path. “They didn’t really have an electoral mandate, but also [they] wanted to do these very broad-reaching, and politically controversial things,” says Professor Staniland. The demands for root-and-branch reforms ran into headwinds, though, as the economy sputtered and public disorder surged.

Still, polls suggest that Bangladeshi voters are optimistic overall about the political transition. An International Republican Institute poll of nearly 5,000 adults taken in the fall found 70% approval of the interim government. Compared with an April 2023 poll, the proportion who said the country was going in the right direction rose from 44% to 53%. Nine in 10 respondents said they would vote in Thursday’s election.

New political landscape emerges

The last time Bangladesh held a multiparty election that was judged as fair and free was in 2008.

In a country of 175 million, and where about half the population is under 30, this means tens of millions of eligible voters have never known a credible election. Its 127 million registered voters also include Bangladeshis who live overseas and have been allowed to cast postal ballots for the first time.

For young voters, “this is a new experience for them. They’re quite excited to cast their vote,” says Mr. Alamgir, the BNP official, in an interview between campaign stops.

He was first elected in 2001 in his home district in northern Bangladesh, near the Indian border, where he taught economics at university. After 2008, the seat was held by Ms. Hasina’s Awami League; its most recent occupant was jailed over his alleged role in the 2024 crackdown. The interim government has barred the Awami League from contesting this election, a decision that has benefited the BNP as the largest opposition party.

Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters

Bangladesh Nationalist Party leader Tarique Rahman gestures to supporters during a campaign rally in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Feb. 9, 2026.

Mr. Alamgir served as a minister in a BNP government led by the late Khaleda Zia, the bitter rival of Ms. Hasina and, like her, the scion of a political dynasty. Now, the party leadership has passed to Ms. Zia’s son, Tarique Rahman, who returned to Bangladesh in December after living in Britain for 17 years. (Ms. Zia died on Dec. 30.)

Mr. Rahman left under a cloud of corruption allegations that he said were politically motivated. Since the fall of Ms. Hasina, all charges against him have been dropped, paving the way for him to stage a triumphant homecoming. He is widely seen as the front-runner to be Bangladesh’s next prime minister.

Mr. Alamgir admits that the BNP failed in the past to prevent corruption but says that this will change as political reforms take root. “What we need is democracy to function,” he says, noting that it is Parliament’s job to hold parties accountable.

More than 50 parties are registered for the election, which will also feature more than 200 independent candidates, including a former beauty queen and a campaigner for urban sanitation.

But the BNP’s main competitor is Jamaat-e-Islami, a right-wing Islamist party that was suppressed under Ms. Hasina. It has formed an 11-party alliance to contest the election. In the IRI poll, 33% of “very likely” voters said they would choose BNP, ahead of 29% who supported Jamaat, while 18% said they didn’t know or declined to say.

The Jamaat-led alliance includes the National Citizen Party, founded last year by students who led the 2024 uprising. Its decision to join caused uproar as women in particular objected to an alliance with conservative Islamists and accused its leaders of betraying the party’s progressive ideals. Several prominent women quit, and some are running as independents. The NCP has defended its decision as pragmatic because it lacked the support to win many seats on its own.

This fallout shows how hard it is to build a party out of a movement led by activists of different political stripes, says Taqbir Huda, a human rights lawyer. To succeed, he says, “you really need to ideologically align on a project that is prescriptive, and not just disruptive.”

Mahmud Hossain Opu/AP

Muhammad Yunus, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and the head of Bangladesh's interim government, listens to an audio recording of ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's phone calls at the July Mass Uprising Memorial Museum, once Ms. Hasina's official residence, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Jan. 20, 2026.

Choices on the ballot

The absence of the Awami League, a fixture of Bangladeshi politics since before the country’s founding, has raised questions about how its supporters will vote and how many will stay home.

In public comments, Ms. Hasina has railed against the interim government and rejected calls to accept responsibility for the bloodshed during the uprising. In November, she was sentenced to death in absentia by a court in Bangladesh for her role in the killings. India declined to extradite her to stand trial, which has strained that country’s diplomatic relations with Bangladesh.

A source close to the former ruling family said that the Awami League knows it has no electoral future until it moves on from Ms. Hasina. But she has resisted the idea of naming a successor, even after her conviction made it almost impossible for her to return home. “She still thinks she’s the prime minister,” says the source, who didn’t want to be named for fear of being ostracized.

The day after his rallies, Mr. Alamgir headed to Dhaka, an eight-hour drive. There, he stood on stage with Mr. Rahman for the launch of the BNP’s manifesto, which includes promises to create jobs, improve governance, and support farmers. Parties have put more stock in promoting their manifestos in this election than in the past – an indicator, say analysts, that voters now expect tangible results from their political representatives.

At a river sluice gate outside Thurakgaon, locals gather near sunset to take photos and eat snacks. The whirligig of national politics and the imminent election feel distant.

Mohammad Shuvo, a second-year philosophy student, buys a pack of nuts from a vendor. He plans to vote for the NCP in the election, which will be his second. The last one, in 2024, his only option was the Awami League. Today, he sees a real choice on the ballot and a chance for Bangladesh to deliver on the promises of the 2024 reform movement in which he participated.

“Now, I have the freedom to vote,” he says. “I can also speak freely about it.”