LISTEN TO STORY

WATCH STORY

By Adolf

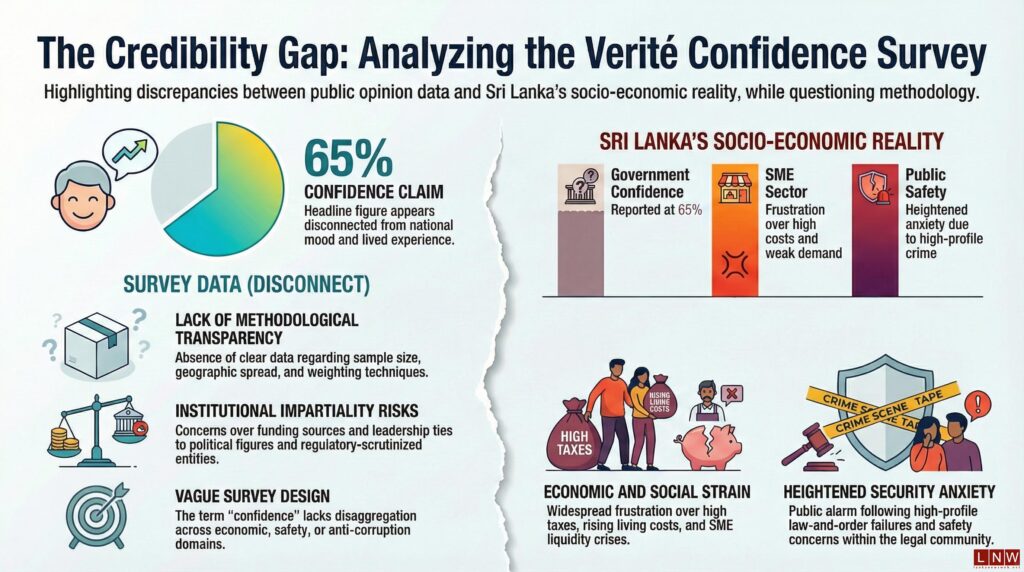

Public trust surveys play an important role in democratic societies. They provide snapshots of public opinion, influence media narratives, and sometimes shape investor sentiment. However, when the methodology, funding sources, or governance of the institution conducting the survey are called into question, the credibility of the findings can quickly erode. The recent survey by Verité Research claiming that government confidence stands at 65% has become a case in point.

The controversy becomes even sharper when viewed against prevailing realities. At a time when the country is grappling with serious law-and-order concerns—including the shocking killing of a lawyer and his wife in broad daylight—public anxiety is visibly heightened. The strong reaction from the Bar Association of Sri Lanka, one of the nation’s most influential professional bodies, underscores the depth of concern within the legal community about safety, governance, and accountability.

Economic pressures remain intense. The cost of living continues to strain households, tax burdens have not eased meaningfully, and small and medium enterprises (SMEs), widely regarded as the backbone of Sri Lanka’s economy, are voicing frustration over tight liquidity, weak demand, and high operating costs. Public protests and sectoral agitation suggest widespread dissatisfaction rather than broad-based optimism.

Against this backdrop, a 65% confidence rating appears disconnected from lived experience. Surveys must not only be statistically sound but also contextually plausible. When macro indicators—rising prices, high taxes, business closures, and public security concerns—point toward strain, a headline figure invites scrutiny. Observers are compelled to ask whether the sample was fully representative, whether dissenting voices were captured, and whether the question framing allowed for nuance.

Public confidence is rarely a single-dimensional metric. Citizens may appreciate certain stabilisation efforts while simultaneously expressing dissatisfaction over crime, taxation, or economic hardship. Without breaking down the data into specific domains—economic management, public safety, governance integrity—an aggregate percentage risks oversimplifying a complex national mood.

Equally important is the credibility of the institution itself. First, the issue of sample size and representativeness has been widely criticised. In a country of over 22 million people, any credible national survey must demonstrate geographic spread, demographic balance, and statistically sound sampling techniques. Without transparency regarding the sampling frame, margin of error, weighting methodology, and response rates, public trust in the findings is severely undermined.

Second, funding transparency matters. While many think tanks receive donor support from NGOs or private entities, credibility depends on full disclosure and safeguards against influence. If funding is linked to advocacy-oriented NGOs or private sector actors with potential policy interests, the perception of bias becomes inevitable, particularly in a politically polarised environment.

Third, institutional leadership shapes public perception. The CEO of Verité Research has been described as a controversial social entrepreneur, engaging with multiple political parties over time. While cross-party engagement is not inherently problematic, public commentary on political actors, shifting alliances, or business associations under regulatory scrutiny weakens the perception of neutrality. Public confidence in survey results depends on visible independence and professional distance from both political and commercial interests.

Suggestions that senior political figures, including the current Prime Minister, may have had past professional associations with the think tank further complicate the perception of impartiality. Even if these affiliations were historical and legitimate, institutional distance is critical when conducting politically sensitive approval surveys. The public must be assured that conflicts of interest—real or perceived—do not shape research design or interpretation.

Finally, survey design itself matters. Asking whether respondents have “confidence in the government” can produce widely varying interpretations. Does “confidence” refer to economic recovery, inflation management, anti-corruption measures, political stability, or personal approval of leadership? Without clear framing and disaggregation, a single aggregate percentage obscures complex public sentiment. Ultimately, the debate surrounding this survey reflects a broader challenge in Sri Lanka’s public discourse: rebuilding institutional trust. Opinion polling must meet the highest standards of transparency, methodological rigour, and independence to contribute constructively. Otherwise, even well-intentioned research risks dismissal, ridicule, and further polarisation. If confidence truly stands at 65% and the government genuinely believes this survey, the ultimate test would be to conduct Provincial Elections—allowing the public to confirm or challenge Verité Research’s findings.

The post Why the Verité Survey is a Public Joke? appeared first on LNW Lanka News Web.