Central banks making banks richer at a loss to tax payers? Monetary independence questioned

Article’s Background

World over, the monetary policy independence of central banks has now come under heavy attack. The major reason is their inability to assure the post-pandemic price stability despite the underlying monetary theory. Devastating effects of high interest rates policy adopted during the past two years on both real sector and financial sector have deterred the recovery of global supply chains and bottlenecks caused by the pandemic and subsequent geopolitical issues. As a result, livings standards are eroded while a new global waive of poverty has surfaced. The debt and foreign currency crisis confronted by the developing world has become the new conduit for the geopolitics and poverty.

The fact of the matter is the inability of central banks to tame inflationary pressures despite sky rocketed interest rates. In this background, not only independence but also instrument suitability of monetary policy are now being questioned.

While the suitability of policy interests as only instruments to drive the monetary policy for price stability is questioned in general, the rationale of interest rates paid by central banks on reserve balances held by banks at central banks as a key element of monetary policy is specifically questioned on the resulting losses to tax payers. This has come up recently at the Treasury Select Committee of the UK Parliament that has questioned why tax payers have to bear the cost of payment of such interest by the Bank of England (BOE) to profit-making banks.

Therefore, this short article is to question the policy rationale of central banks paying interests on reserve balances as part of the monetary policy based on concerns raised by the UK Treasury Select Committee as revealed in an article published in “The Telegraph” website on 01 May 2024 (Read the article here). Accordingly, concerns over possible insider dealings behind the interest rate policy of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka are also raised in this background.

Central bank interest rate on bank reserve balances

Central banks operate policy rates in various forms varying on lending to banks in the case of deficit liquidity and mopping up funds from banks in the case of excess liquidity. The main idea of policy rates is to target the overnight inter-bank interest rates in a corridor preferred by central banks in their monetary policies. It is this overnight inter-bank interest rate that central banks use as the monetary weapon to tame inflation or keep price stability.

While central bank lending rates set an upper limit for the inter-bank rate variability, interest rate payable on overnight reserve balances is expected to set a floor for it. This is simply the price control mechanism of central banks.

Accordingly, inter-bank interest rates are expected to vary within the policy rates corridor. This is assured by central bank monetary operations or open market operations (OMO) that are carried out to intervene in bank liquidity levels used to fill the gap between outflows and inflows of day-to-day bank funds/cash which are settled through reserve balances of banks at central banks.

Accordingly, central bank OMOs are nothing but filling liquidity gaps of banks connected with credit creation-based business operations. As nobody has empirical research findings to confirm the link between inter-bank interest rates and price stability and underlying policy transmission, the only model of monetary policies evident from central bank is to support day-to-day bank liquidity management in order to protect public trust in banks on credit creation based business.

Therefore, reserve balances represent the most active part of central bank monetary liabilities or money printed by central banks. The other part is the currency held by banks and public to be used for settlement of payments in cash outside central banks.

The key concern raised over this type of interest rates corridor-based OMOs is that why central banks want a floor by paying interest on bank reserve balances despite they are the current accounts of banks maintained for transactions purposes. The issue here has two facets.

- First, why central banks pay interest through money printing on bank current account balances while banks do not pay interest on customer current accounts. In addition, such interest payments will discourage banks from lending to customers at around these interest rates.

- Second, why central banks want a specific floor for overnight inter-bank rates because central bank lending rates alone will effectively guide inter-bank rates. In general, central bank lending rates provide for a base around which inter-bank rates will vary as central banks will reduce the interest rate variability by lending/supply of reserves or liquidity to banks. That is the crux of the present models of inter-bank interest rate target-based monetary policy.

Concerns over Bank of England

The Bank Rate or base rate is the overnight interest rate paid by BOE for bank reserve balances on a daily basis. Banks also can borrow at few basis points above the base rate for shortages of liquidity. It is this base rate that the BOE decides in the monetary policy. The BOE has raised the base rate 14 times in this tightening cycle so far for a total increase of 5.15% from November 2021 (i.e., from 0.10% in November 202 to 5.25% at present).

According to the said article, major concerns over interest payment at base rate are as follows.

- Four large banks have been paid around a striking amount of money of £ 9.3 bn in 2023 as compared to £ 3.9 bn in 2022. Banks have a habit of parking excess funds at the BOE for receiving a risk free income.

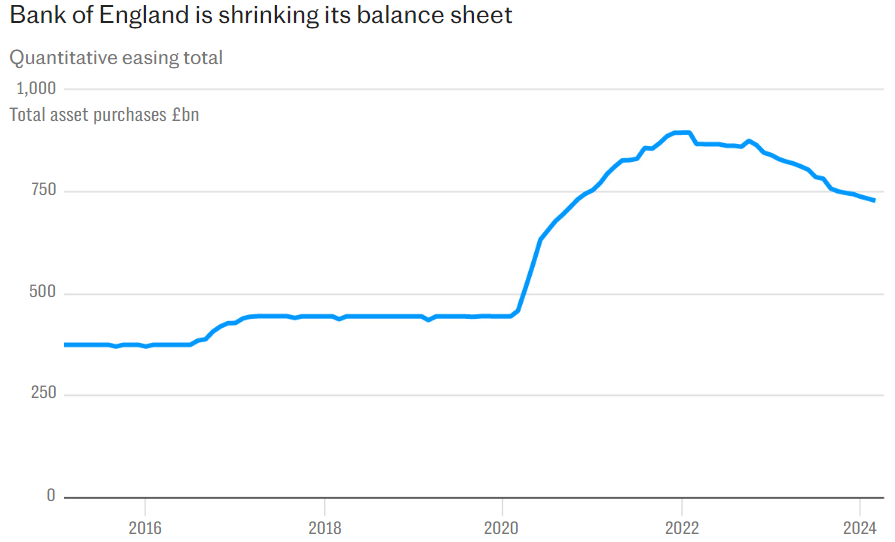

- When interest rates are high, the BOE generally has to pay more on reserve balances than it receives on lending to banks. This has happened because new money pumped for the purchase of bonds from high street banks by the BOE under pandemic-driven quantitative easing has been parked in reserve accounts which received high interest rates in 2023 due to very tight monetary policy.

- In terms of the agreement reached in 2012 between the Treasury and BOE under the independent monetary policy, the Treasury is to reimburse the loss incurred by BOE on its OMO bond portfolio while the profit is remitted to the Treasury. The reimbursement for the loss in 2023 is expected to be around £ 100 bn. Therefore, interest payment on reserve balances is a cost to tax payers under the independent monetary policy.

Accordingly, opinions are expressed whether the government should review the present monetary policy model of the BOE in the interest of tax payers.

Money printing loses of the US central bank

Similar concerns are raised on the Federal Reserve of the US (Fed) as it has reported a loss of US$ 116 bn in 2023 due to the interest paid on bank reserve balances higher than interest income received on lending/liquidity facilities to banks.

This is an outcome of the fastest phase of quantitative easing during the pandemic as well as the fastest phase of post-pandemic policy rates hike reported from the Fed. As a result, the Fed’s increase in money printing/asset purchases was 114% from the end of 2019 to mid 2022 (increase from US$ 4,174 bn to US$ 8,939 bn.). The post-pandemic rate hike has been 5.25% so far, i.e., 11 times from 0-0.25% to 5.25%-5.50%. At present, the Fed pays interest on overnight bank reserve balances at 5.4% while lending at 5.5%.

Concerns over Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CB) policy

The CB’s policy rates corridor is the rate on Standing Lending Facility (SLFR) and the rate on Standing Deposit Facility (SDFR) on overnight basis. In addition, the CB offers repo (moping up reserves) and reverse repo (injecting reserves) auctions to intervene in specific location of overnight inter-bank interest rates within the corridor. The corridor at present is 9.50% and 8.50%.

However, the CB imposed arbitrary ceilings on these facilities in January 2023 with a bizarre motive of activating the inter-bank market on bank own funds and reducing market interest rates accordingly without policy rate cuts. The said ceilings were as follows.

- Standing deposit facility to any bank is maximum 5 times a month.

- Standing lending facility to any bank any day is maximum 90% of the statutory reserve requirement of the bank.

According to CB’s annual financial statements released last week, accounting side of the monetary policy and connected financial management reveals several concerns.

- The cost on SDFR has been Rs. 15.9 bn in 2023 as compared to Rs. 29.9 bn in 2022. The total turnover of standing deposits stood at Rs. 17,889 bn in 2023 with a daily average of Rs. 74 bn. as compared with Rs. 51,934 bn and Rs. 224 bn, respectively, in 2022. Despite the significant reduction in standing deposit volume in 2023, the high SDFR (15.5%, 16.5%, 14.0, 12.0%, 11.0%, 10.0%, etc.) has contributed to still high volume of interest payments.

- Another concern here is the implementation of SDFR without relevant legal provisions to pay interest on excess reserve balances of banks. However, a legal provision is available to pay interest on statutory reserve balances.

- The ceilings or restrictions on standing facilities in 2023 have caused the CB to frequently conduct reverse repo auctions to pump new liquidity at rates lower than SLFR. As a result, the CB has pumped a total of Rs. 10,186 bn with an auction average of Rs. 40 bn. The loss due to offer of overnight reverse repo auctions at rates lower than the SLFR is estimated to be around Rs. 11 bn in 2023. In addition, the CB has offered a special liquidity facility to banks in 2023 and earned Rs. 16.7 bn of interest income while interest income on reverse repos and SLFR was about Rs. 51.5 bn as compared to Rs. 117.8 bn in 2022.

- Overall, it is evident that banks have benefitted from all monetary policy measures, i.e., standing facilities, reverse repo auctions and special liquidity facility to strengthen their profit during 2023. For instance, commercial bank sector has reported an increase in pre-tax return on assets to 1.6% in 2023 from 1.2% in 2022, despite the increase in the impaired loan ratio to 13.0% in 2023 from 11.5% in 2022.

- Meanwhile, interest income on holdings of government securities has risen to Rs. 522.5 bn by 46.1% over Rs. 357.2 bn reported in 2022. As a result, the cost to tax payers on public debt due to CB’s high interest rates policy is unbearable. The cost to tax payers is significant as the CB could not remit a single cent of dividend to the government in 2023 whereas the capital of the CB plummeted to Rs. 11 bn in 2023 from Rs. 82 bn in 2022 consequent to the erosion of CB reserves due to the loss of Rs. 114.4 bn reported in 2023.

Therefore, the conduct of money printing business independently by the CB at a loss to tax payers could raise concerns similar to other loss-making state enterprises that are listed for privatization to ease the pressure on fiscal policy front.

The CB is already a bank privatized to few individuals to manage as they wish with or without profit on asset portfolio of around Rs 4.5 tn funded by tax payers’ money at a loss of Rs. 114.4 bn in 2023. Therefore, our lawmakers must rethink whether this is the central bank we need for the bankrupt economy.

In spite of such adverse concerns over CB financial operations, it is questionable why the Auditor General and CB Governing Board have confirmed as follows.

- Auditor General – based on the audit procedure followed, the CB has procured and utilized resources economically, efficiently and effectively. I wonder whether the Auditor General had any idea of nature of monetary policy connected costs and losses sated above.

- Governing Board – It has assessed the key financial risks impacting the CB as disclosed in the financial statements and has determined that there are no material uncertainties that may cast significant doubt about the CB’s ability to continue as a going concern. I wonder whether the Governing Board had that kind of luxury to assess the financial impact of the monetary policy/OMOs implemented in terms of decisions of the Monetary Policy Board, given its unknown risks and uncertainties and arbitrary responses by Monetary Policy Board.

Few remarks to resolve national concerns

- For upcoming national elections, it is reported that political leaders offer various national policy visions and models to upgrade living standards and happiness of the public from the present bankruptcy.

- However, nobody seems to propose how respective development visions and models are financed, given the independent central bank monetary model of managing the day-to-day liquidity of banks with losses passed to tax payers. Instead, they only talk about getting concessions to recommence foreign debt in default for more than two years.

- However, concessions envisaged are only debt politics that have nothing to do with financing for development models. Therefore, if national leaders are really interested in economic welfare of the general public in the bankrupt economy, they must think of how they would revamp the central bank and its monetary policy to drive the monetary and financial system to fund such development models. This is the humanity we require from democratic politics in this century. This requires

- removal of tribal monetary hypotheses that are used at present to control operations of central banks despite losses to tax payers and livings standards and

- diversify policy instruments to provide a greater/fair distribution of credit and finance across sectoral economic activities at different risks against the current monetary model of policy rates-based printing of money to help bank dealers manage their day-to-day liquidity gaps.

- However, it is doubtful that the CB would allow it similar to the plight of Liz Truss government in UK towards the end of 2022. In that context, all development models proposed without financing models will only be false political promises for votes.

This article is released in the interest of participating in the professional dialogue to find out solutions to present economic crisis confronted by the general public consequent to the global Corona pandemic, subsequent economic disruptions and shocks both local and global and policy failures. All are personal views of the author based on his research in the subject of Economics which have no intension to personally or maliciously discredit characters of any individuals.)

P Samarasiri

Former Deputy Governor, Central Bank of Sri Lanka

(Former Director of Bank Supervision, Assistant Governor, Secretary to the Monetary Board and Compliance Officer of the Central Bank, Former Chairman of the Sri Lanka Accounting and Auditing Standards Board and Credit Information Bureau, Former Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Institute of Bankers of Sri Lanka, Former Member of the Securities and Exchange Commission and Insurance Regulatory Commission and the Author of 12 Economics and Banking Books and a large number of articles published.

Source: Economy Forward