Sri Lanka’s Presidential Election Reflected a Regional Divide

Sri Lanka’s September 21 presidential election – the first since the protests in 2022 that ousted former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa – has been praised for the lack of election violence and the peaceful transfer of authority. This does not mean that the victory of Anura Kumara Dissanayake (often referred to by his initials, AKD) of the National People’s Power (NPP) reflected a political consensus.

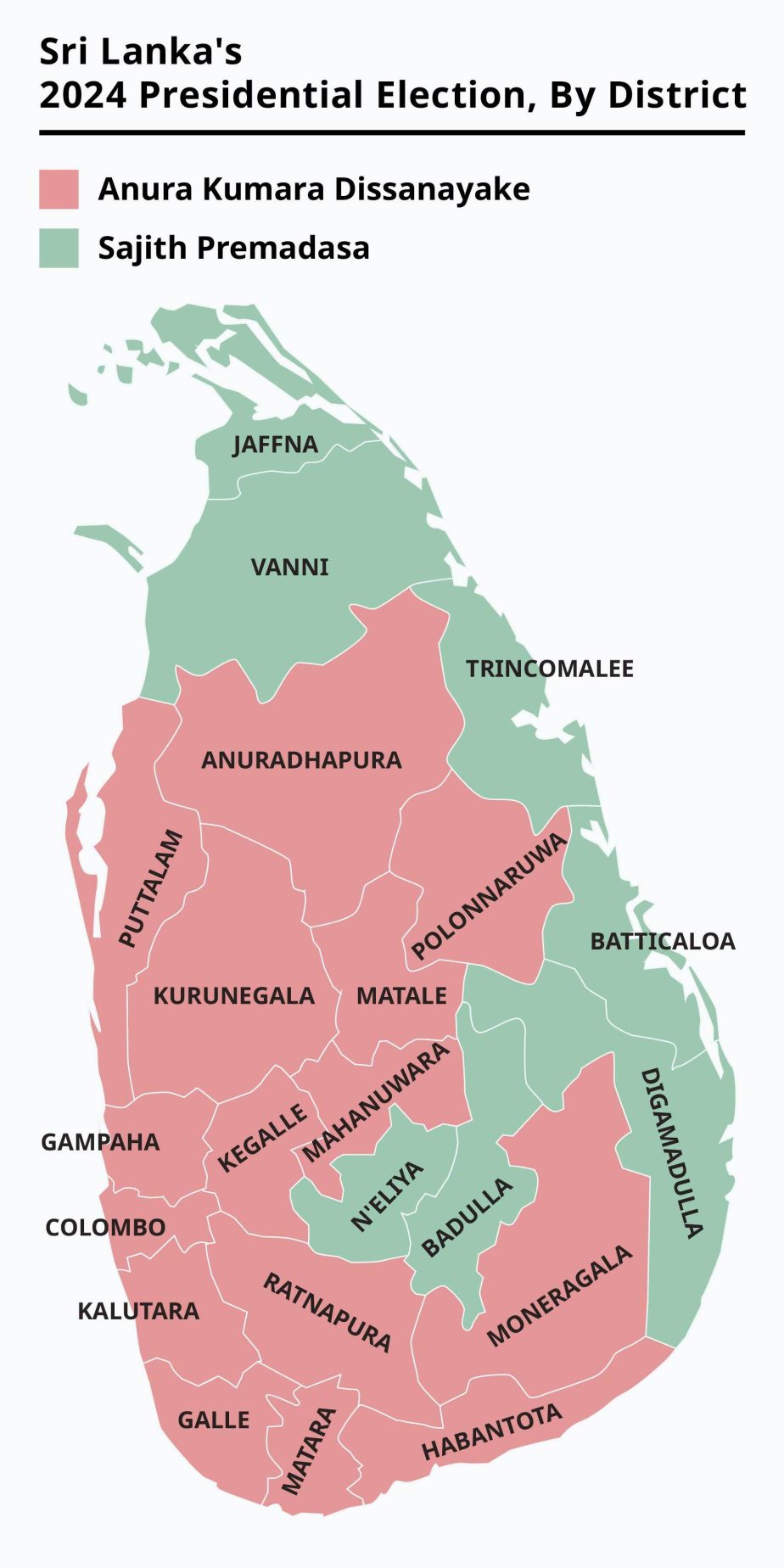

At first look, the election reflected a divided country: the South-West for Dissanayake and the North-East for Sajith Premadasa of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB). However, on closer inspection there is more to unpack here as Dissanayake has made key inroads. Nevertheless, this division can also be seen as a mirror: the South’s rejection of the political elite is also occurring in the North, opening the field for more radical possibilities.

Main Observations

Sri Lanka has a preferential voting system that holds three counts simultaneously. Dissanayake received 42.31 percent of the vote in the first count and 105,264 votes from the second count to become the ninth executive president of Sri Lanka. His main rival, Premadasa, received 32.76 percent of the vote and the incumbent president at the time, Ranil Wickremesinghe, received only 17.27 percent.

In the protests in 2022, people called for an end to Sri Lanka’s existent political culture and articulated a frustration with the old political elite. In this election, Sri Lanka’s traditional political parties such as the United National Party run by the Wijewardene-Wickremesinghe family and the Sri Lanka Freedom Party run by the Bandaranaike family barely made a dent, as people voted for either the NPP or the SJB.

The Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), formed in 2016 in mimicry of the old parties by the Rajapaksa clan, is in particularly dire straits. Despite winning 52.25 percent of the vote in the presidential election in 2019 and a supermajority in the parliamentary election in 2020, the SLPP’s presidential candidate, Namal Rajapaksa, received only 2.57 percent of the vote this year.

While Dissanayake’s victory is confirmation of the NPP’s popularity as an alternative to the old political elite, some remain unconvinced of people’s investment in the party itself. Political economist Devaka Gunawardena is one of the skeptics.

“We have to be careful in distinguishing genuine support for a party and the floating voter conundrum,” he said. “A lot of the people who voted for Gotabaya Rajapaksa in 2019 switched over to the NPP-JVP in 2024. Clearly, they were frustrated with the direction the country was headed in, especially economically. I see this as a protest vote.

Gunawardena added: “The NPP-JVP’s ability to retain these voters depends a lot on their policies and the actions they take to provide meaningful relief to the people, in addition to offering a genuine prospect of recovery from the economic crisis. The NPP-JVP does not have a lock on this vote base. If the NPP fails, the same voters could move to another party.”

Upon Dissanayake’s victory, social media exploded in response. A number of narratives could be seen, such as elitism about Dissanayake, sexism about the recently appointed prime minister, and pro-NPP mania from the South.

Unlike in the South, Premadasa topped the polls in the Northern, Eastern and Central provinces. However, there was a noticeable decline in his popularity from 2019 to 2024. In 2019, he fielded 41.99 percent of the vote but this year, he secured just 32.76 percent.

In response to the North-East’s rejection of the NPP, social media users leveled a number of racist claims about Tamil people. They criticized the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK)’s hold on their constituencies, called the party feudalistic, and referenced Tamil militancy, painting all Tamil people as terrorists or extremists.

“The NPP supporters are on social media asking people to put their criticisms aside. Everyone understands that this government has just been elected and that they need time. But these supporters have to also understand that no one needs to put their complete trust in the NPP,” said Anushani Alagarajah, executive director of the Adayaalam Centre for Policy Research.

“We did this before in 2015 for the yahapalanaya (i.e. Good Governance Government). We kept expressing our skepticism and nobody in Colombo listened to us. They expected us to trust the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe alliance, but in the last years, Colombo turned around and criticized them heavily for not meeting their expectations. They are doing the same thing today.”

“Some NPP supporters, acolytes, and propagandists are in a social media echo chamber and refusing to hear the reasons why others are concerned or even critical of the NPP’s stance on some key issues,” added Balasingham Skanthakumar, co-editor of Polity. “Any political party needs to keep a check-on itself if it wants to stay on in power.”

Northern Province

In the Northern Province, Premadasa received the most votes, but the votes were split fourfold. Pakkiyaselvam Ariyanethiran, the Tamil “common candidate,” performed better than expected: He came second place in Jaffna with 31.39 percent of the vote and third place in Vanni with 16.74 percent. On the national level, he placed fifth, with just 1.7 percent of the vote. Wickremesinghe came in third place in Jaffna with 22.7 percent of the vote and second place in Vanni with 16.74 percent.

Dissanayake came in fourth place in both districts.

“The clear mandate that the Tamil people have given is that they did not choose Dissanayake. They voted for everyone but Dissanayake,” Alagarajah said. “The NPP can’t misinterpret this, but they can actually try to understand the mandate they received [by asking]: Why did the North-East not vote for us?

Sivakar, 30, a software developer based in the Northern Province, had another perspective: “Rejection and acceptance happens if there are only two candidates. This election had multiple candidates. Premadasa, Wickremesinghe, and Dissanayake made important inroads.” He said that NPP’s breakthrough was based on populism.

He saw a number of reasons for the SJB’s overall popularity: ITAK recommended Premadasa as the best candidate and the SJB had a decent team.

Another important element is reach. Sivakar did not hear much from or about the NPP in the North. In the last presidential election, the NPP had only 3.16 percent support. Many believed this could increase to around 20 percent but not more. Most of the pro-NPP discourse from the North existed in a bubble online and on social media.

Last but far from least, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) – the central party in the NPP coalition – has a history of racism. It launched an insurrection in opposition to the Indo-Lanka Accord of 1987, opposed the peace process in Eelam IV, and supported the Sinhala supremacist Mahinda Rajapaksa. The NPP-JVP has not made concessions to the North-East for these positions in the past.

“People ignore the history of the JVP and expect us to look at it as just the NPP. This standard is not applied to anyone else. Imagine if it had been a Tamil rebel, a Muslim person, or a criminal. Why then dismiss only JVP’s past and not the other’s past?” Alagarajah said.

At present, the NPP focuses on equality for all, but mere lip-service will not tackle the country’s culture of majoritarianism and the structural and institutional inequalities in place. The NPP has not facilitated discussions about the National Question or reconciliation beyond their commitment to the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. They have a limited number of Tamil or Muslim members in either their Politburo or their Central Committee.

The NPP’s behavior once elected only confirmed the suspicions many Tamil sources held. Dissanayake’s speech did not have subtitles in Tamil, one of the country’s national languages. He also appointed accused war criminals into key positions such as the secretary of defense.

Eastern Province

In the Eastern Province, Premadasa received the most votes because of the support he received from the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress and All Ceylon Makkal Congress.

While Dissanayake received less votes than Premadasa, the inroads he made in the Eastern province are important. In Ampara, Dissanayake’s votes increased from 7,460 in 2019 to 108,971 in 2024. He came third in Batticaloa and Trincomalee, but his vote bank has similarly increased. At the divisional level, in Kalmunai, Dissanayake’s votes increased from just 213 in 2019 to 10,937 in 2024.

A. Rameez, former vice chancellor of South-Eastern University and a professor of sociology, noted that despite the overall result Premadasa received, the youth of the Eastern Muslim community seem to favor the NPP.

“The youth, such as the millennials, have more access to the political landscape,” Rameez said. “They have a very good impression of the NPP. They prefer their policies. They seem to like policies such as an end to MPs pensions and the removal of permits. The youth played a pivotal role in changing the dynamics of the Eastern Muslims this time. Though the overall vote is minimal, the number is a comparable increase to the previous election.”

Central Province

Nuwara Eliya in the Central Province is home to the Malaiyaha (Hill Country) Tamil community. In Nuwara Eliya, Premadasa won the largest share of the vote at 42.58 percent. The Tamil Progressive Alliance backed him in his bid for the top-seat. Wickeremesinghe came second, fielding 29.25 percent of votes. The Ceylon Workers Congress (CWC), National Union of Workers, and Member of Parliament Velu Kumar backed the incumbent president. Dissanayake came third, but unlike Premadasa and Wickremesinghe, did not receive the backing of any major political party in the community.

“While Dissanayake placed third, fewer than 100,000 votes separated him and Premadasa in the Nuwara Eliya division. With that in mind, researcher Letchumanan Kamaleswary said, “the media’s visualization of it [the result] is incorrect. What they failed to do was compare the number of votes Dissanayake received in 2019 and then in 2024. There is an increase for Dissanayake and the NPP so it is not a pure rejection.”

Dissanayake won 5,891 votes in Nuwara Eliya in 2019 and this increased to 105,057 votes in 2024. Like in the Northern and Eastern Provinces, young people campaigned for and voted for Dissanayake.

“The young people that blindly support Dissanayake do not try to think about ethnicity. As a result of the pandemic and economic crisis, they are concerned about their basic needs. They need an instant solution to the economic issues: poverty, unemployment and support for their businesses,” Letchumanan said.

The economic crisis hit the Malaiyaha Tamil community the hardest. Despite speeches by Dissanayake that linked class and ethnicity, the NPP as a party did not pursue the votes of the Malaiyaha Tamils properly. Their manifesto made minor recommendations about the community’s concerns.

The Malaiyaha Tamil community, for instance, has been demanding an increase of their daily pay from 1,000 to 1,700 rupees. Dissanayake has been deflective about this and has said that immediate action cannot be taken to resolve this issue. He responded in a similar fashion to the demand for land reform, despite independent research that confirmed that 20 perches of land (505.8 square meters) can be provided to 150,000 families.

“Either the NPP is oblivious to this fact or they seek to deny the Malaiyaha community land… His response might have been different if he had been asked about Sinhala families that need access to land,” Letchumanan said.

End of Old Political Parties

While the results portray a divided country, the dividing line also acts as a mirror: similar to the South, the old political elite in the North-East are in decline.

While Ariyanethiran performed better than expected, Tamil nationalist parties are losing support. Many of these parties have made a number of promises but have never achieved them. One of the main criticisms people have made is the prioritization of Tamil nationalism over the economic crisis. With the NPP’s victory, a number of discussions have started about alternate options in the Tamil homeland.

“They talk about political remedies and political rights. But there have been no results,” said Jeyatheepa Punniyamoorthy, former commissioner of the Office on Missing Persons. “We need political rights, but people also deserve development in our areas too. We need to fulfill our daily needs. We can then think about education, employment and political or system change. People at the top tiers of society can think about political rights and system change.” Jeyatheepa is a victim of enforced disappearances and she has been searching for her husband for 15 years.

In the past, Sri Lanka’s Eastern Muslims looked to the Muslim parties for representation, but more and more see these parties as failures, motivated by self-interest.

“These days people are frustrated with all the politicians, including the Muslim politicians,” Rameez said. “They believe that these politicians have deceived them. They use the mandate of the people to receive perks and privileges in national governments. Soon after they receive their votes, they compromise their initial promises to meet their personal priorities.”

Similarly, members of the Malaiyaha Tamil community are tired of family-run trade unions and political parties. For example, the CWC, headed by Jeevan Thondaman, has been run by the Thondaman family since 1939. At every tier of the party is a family member and nominations at the provincial and local level are only handed out to family members. The CWC also collects union fees that finance their opulent lifestyles and decadent habits, even as their constituency is impacted by external shocks like the pandemic and the economic crisis.

Another problem is representation. Within the Tamil nationalist parties, women are recruited for political campaigns and speeches, but they rarely make decisions or hold leadership positions. In the Malaiyaha Tamil community, female representatives are invited for functions as decorations and entertainment. Women are also part of the trade unions, but play traditional roles such as attending puberty ceremonies.

The Future

At the moment, the NPP has been eyeing candidates in the North-East. If the NPP receives a similar turnout in the parliamentary elections scheduled for November 14, it cannot realize its promised reforms around anti-corruption and an end to austerity. A simple majority of 113 seats is needed if the party is serious about governance. In Sri Lanka, coalition governments have proved to be unstable, as the recent yahapalanaya in 2015 proved.

While it may not be obvious, both the South-West and the North-East of the country are united around one cause: justice. The South-West cries out about economic injustice as the North-East cries out about decades of institutional and structural racial injustice. These forms of injustice impact both sides: tools of oppression tried-and-tested in the North-East were used in the South-West to break up protests in 2022, for instance. The impact of the economic crisis is compounded in the North-East as seen in the omnipresent poverty.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the NPP is unable to propose a solution to the National Question, further reconciliation, or provide economic solutions that consider decades of discrimination and oppression. As the old political parties expire, Premadasa’s popularity declines, and the extra-parliamentary left continues to sit on the fringes, the NPP needs an opposition to hold them accountable. This is an opportune moment for the mandate from the North-East to transform into solid representation by local people.