Nilu's health suffered post-birth, but she thought seeking help was a 'weakness'

Key Points

- An estimated one in five new mothers and one in five new fathers experience perinatal depression or anxiety.

- The perinatal period presents difficulties for all Australians, but migrants often face additional challenges.

- Nilu Karunaratne struggled with her mental health after her twins were born, but was hesitant to seek help.

They first moved to Blacktown in Sydney, but later relocated to the small town of Miles in Queensland, where Dharmapala had a job opportunity as a general practitioner.

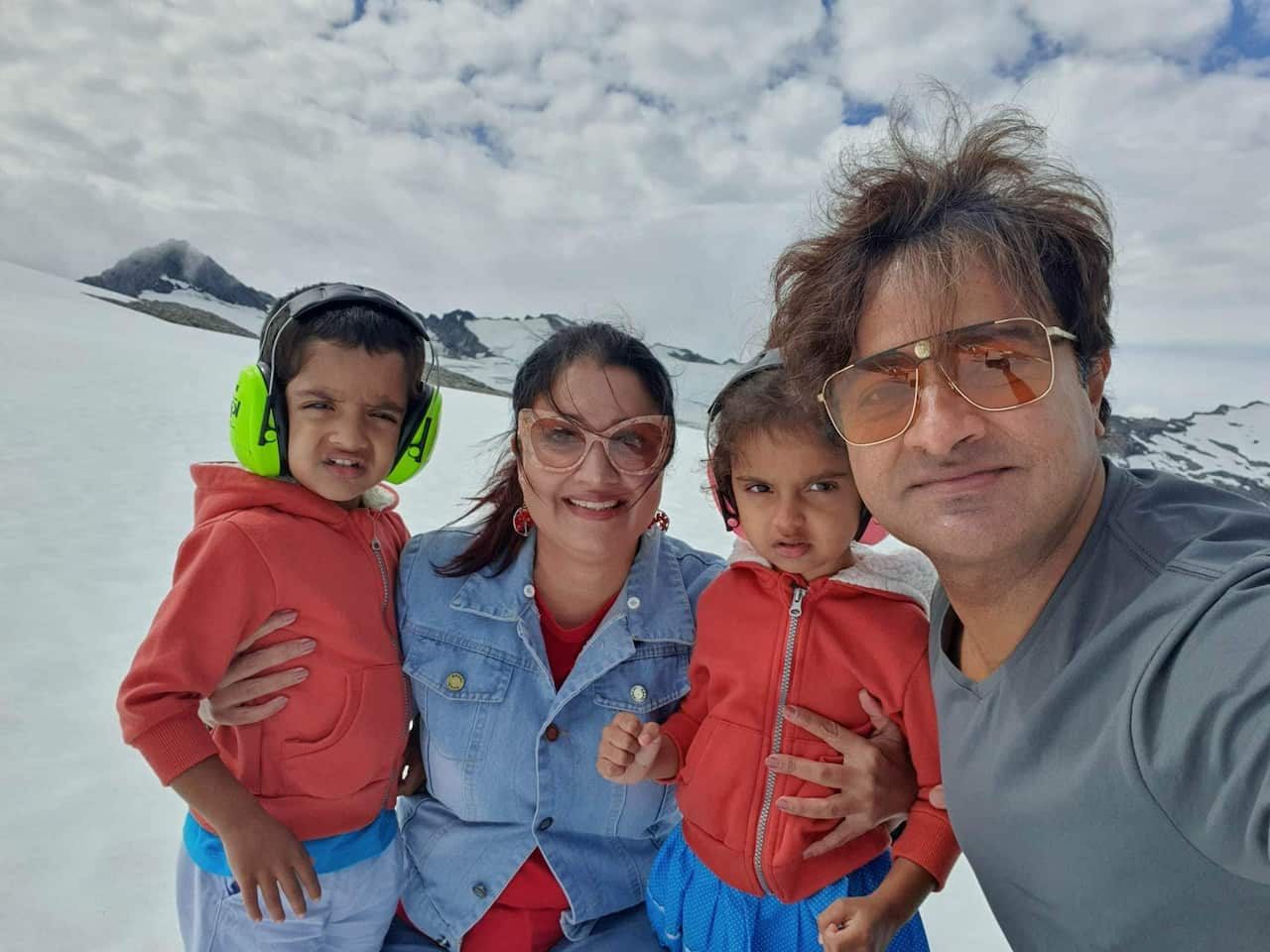

Nilu Karunaratne (second from left) struggled with her mental health after the birth of her twins. Source: Supplied

"I was tired, but I couldn't sleep, and every minor incident triggered anger in me, and tears flowed without any reason."

"We think that seeking help is a weakness but it's not at all — seeking help is a strength, and now I see that."

What is perinatal mental health?

- Symptoms vary from person to person and can include feeling frustrated, angry, sad, hopeless or empty.

- Some people also experience a loss of energy and a lack of interest in activities they previously enjoyed.

- Insomnia, difficulty connecting with the baby, feeling guilty or worthless and even thoughts of death are also common symptoms.

New data has also found two-thirds of new Australian parents don't have a strong support network of other parents, with one in three struggling to connect with other parents.

"And the number is just compounding every year with new parents and expectant parents."

Cultural barriers and isolation

For Karunaratne, becoming a parent in the small town of Miles - which is 340 kilometres west of Brisbane and has a population of 1,874 according to the 2021 Census - was a stark change compared to her old life.

Karunaratne struggled with perinatal mental health and had limited access to support in rural Queensland. Source: Supplied

"It was very difficult."

How can regional and remote Australians access mental health support?

"We know that people in regional, rural and remote communities are at a disadvantage in terms of seeking specialist help simply because it's not available within their areas," she said.

For Karunaratne, appointments with an online psychologist enabled her to take steps to improve her mental health.